|

|

|

[ last updated: 09.28.00 ]

|

|||

|

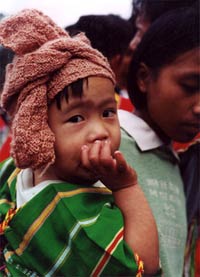

It is through Kyi's organization, Images Asia, that I learn that some illegal Burmese immigrants are working for Thai factory workers on the border. With their families harassed or brutalized, with no jobs available back home, and without the status of "international refugee" granted by the Thai government, these young men and women flee their country to find a way to support their families. It is in the border town of Mae Sot that I actually get a chance to meet them, and hear their stories. We are sitting on the upper level of a traditional Thai home, owned by one of the humanitarian groups that is stationed in this small frontier town. They have donated their house to shelter some of the workers. The floor is smooth teak. A breeze drifts through the open room. Everything is clean. It is a clear day out, and mango and coconut trees sway and creak outside the porch. Were it not for the subject of our conversation, I would think that we were in a tropical resort. Fourteen young people, one of whom is pregnant, come out of the back kitchen and up from the garden, and sit expectant and smiling in a circle around my friends and me. Our translator is an older fellow, who laughs loud and conveys jokes from English to Burmese and back without too much effort. We begin with introductions, and when I ask what the baby's name might be, they laugh. They struggle to pronounce my name, and they think it is the funniest thing in the world when I mispronounce theirs. They laugh longer than I do. They laugh when they talk about being forced to live in the factory compound. They laugh a sort of "can you believe it" kind of laugh. They talk about working between 16 and 20 hours a day, depending on the production order and the demand on the factory owner. When they finish their story, they laugh. They laugh the loudest when they tell us that those who complain about inadequate food and housing are ratted out to the police by the factory owners. The factory owners call in the police to deport the Burmese workers, and the soldiers throw them in prison for being disloyal to the state. They force a smile when they tell me that factory owners fire women for getting pregnant, because it is a distraction from the job. The young pregnant woman stares at the floor. They smile when they tell me that sick children are fired for going to a health clinic, because it draws attention to the factory. They smile when they tell me that they are fired and kicked out of their factory bunker when the machines break down, and the owner has to call in outside maintenance. I try to smile, but it's unnerving. After two hours, they offer to show me what they make. I nod. They all want to see my reaction. They all want to see how I will laugh when they show me what they spend 16 hours a day, 30 days a month, making. They unwrap a five inch, plaster Statue of Liberty. "For you?" one of the younger men offers. I'm not quite sure what to say. They want to give it to my friend Mike and me as a gift, an American symbol for their new American friends. We offer to buy it from them. We offer a thousand baht, knowing that's probably a good month of work for them. They stop smiling and shake their heads "no." A gift needs no compensation. "For the baby with no name," I offer. I smile. This is the first time I've done so through the entire afternoon. There is a pause, as the woman thinks to herself. I wonder what choices she is making: prideful reluctance toward charity versus the ability to provide for her baby? I feel guilty for making her uncomfortable. She smiles back. She takes the money. We laugh. |

BACK TO 9-28 home | back issues | cover designs | about fanmail@turfmag.com